The Postage Stamp Renaissance

This is the story of how a postage stamp, a rocket scientist, and a blind bluesman brought an obscure musical tradition of outer Mongolia to the world.

I'm sitting in a Portland, Oregon rock club. It's situated right smack in the middle of the downtown meat market. To the right of me is Voodoo Donuts. Gutter punks spange outside, grabbing a few bucks from the drunks attracted to the scent of bacon and glazing. To the left of me is a flophouse, the human overflow sleeping in the streets outside it. On a normal night, the club caters to bored frat boys and enterprising bank tellers, everyone dressed in their cleanest polo shirts, Axe so thick it smells like a Thai ladyboy exploded.

Tonight it's different. The club is filled with drifting incense. People crowd the stage, sitting on the floor indian style, necks aching to see the white robed performers. Passers by wander in, hoping for the usual drunken party, and stand struck dumb. The stage is lit from every angle by candles, and in the center sits a massive iron cross. The performers mournfully ascend the stairs to the stage. Which is appropriate, because I have it on good authority that the cross once belonged to a particular headstone in a particular cemetery.

The sound comes then, the groaning, resonant moan that pitches wildly. People glance around, trying to pinpoint the sound's origin. Part didgereedoo, part Gregorian chant, its a sound that doesn't originate so much as emanate from the stage. I turn to my friend, who sits with an ecstatic grin I must be sharing and say: "What is this?"

I'm ahead of myself by at least eighty years. Starting from the top--

If you're Richard Feynman, you're a genius physicist with a penchant for chicanery and the sensibilities of a Bohemian. He spent his spare time at the Los Alamos labs back during WW2 cracking safes, or tricking people into opening them and then claiming them cracked, which is just as good. He collected stamps, and as a stamp collector, the rarer and the stranger the better.

One night he asks a friends and fellow adventurer, "Whatever happened to Tannu Tuva?"

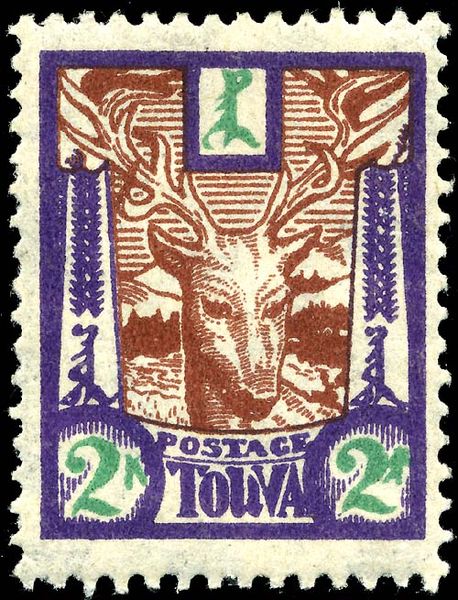

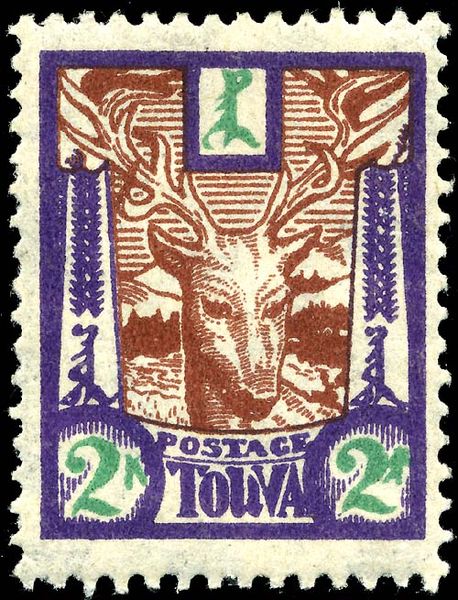

Back in 1927, a set of stamps were issued from the tiny Mongolian prefecture of Tannu Tuva. As a newly independent country, finally wresting their freedom from Imperial China, the next logical step was to issue a stamp. Somehow this stamp made its way around the world and into Feynman's hands.

This stamp stuck out to Feynman-- here, have a look.

Now, that might not be the exact stamp, but you get the idea. He decided that he had to know more about this place. Tannu Tuva -- it sounds like a fantasy realm. In fact, Feynman's friend thought it may well be made up. That was just the sort of thing Richard would do to people. He'd invent a country, a whole culture, and see how long he could trick people into believing in it. Did I mention this man worked on the atom bomb?

What followed that question is recorded in "Tuva or Bust!", by Ralph Leighton. Richard Feynman spent the rest of his life trying to visit Tuva. He collected scratchy field recordings of Tuvan music, old photos of Tuvan costumes, anything he could lay his hands on. He and his friends created the "Friends of Tuva" foundation to archive this knowledge, and it lives on today.

Now keep in mind this was the middle of the Cold War, and a former atomic scientist wanted entry into the Soviet Union. Even if the Soviets wanted him in, the State Department probably wasn't too keen to let an outspoken cultural critic like Feynman anywhere near Russia. And so his requests existed in an endless bureaucratic loop. Perhaps they were hoping he'd forget about it. Never underestimate the memory and tenacity of a man who remembered a postage stamp he'd seen a decade earlier. Feynman never gave up.

Finally the State Department relented. After nearly twenty years, they granted Richard Feynman the right to travel to Tuva.

Unfortunately, Feynman died of cancer the day before.

The world was poorer for the loss, but before he went, Richard Feynman taught thousands, earned Nobel Prizes in physics, became an outspoken proponent of science, and lived life with a wry smile and set of bongos.

Step back a little. There's someone else in this story.

Paul Pena was born with congenital glaucoma. His eyesight was bad at fifteen, and gone by twenty. It didn't slow him down--he learned to play music with an intimidating ease. By the mid seventies, right at the time Ralph Leighton and Richard Feynman were having their dinner discussions, he was playing with anyone who had a name in the blues community. Pick a name out of a hat, and Paul Pena played with them. B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Leon Redbone, Steve Ray Vaughn, Mississippi Fred McDowell, 'Big Bones,' John Lee Hooker and T. Bone Walker-- he even had a song of his recorded by the Steve Miller Band. Paul Pena was going up, and fast.

Then his wife, Babe, got sick--kidney failure. He dropped everything to take care of her. One night, December 29th, 1984 to be exact, Paul was listening to his shortwave radio. This isn't something people do too much these days, but if the air was just right and the night was clear you could hear broadcasts from all over the world. Paul was hunting for a Korean language lesson he'd heard.

Instead, he heard a Russian broadcast centered on the music of Tuva. That when he heard Tuvan throat singing. To a musician, specifically to a blues musician, that rumbling growl must have been a revelation. Two, sometimes three separate tones overlapped in one voice. This became an obsession for Paul.

For the next eight years he searched record stores high and low for this music. He asked musician friends, he tried to explain the unearthly sounds he heard that winter night. For eight years, no one had an answer for him.

It wasn't until 1991 that he found a CD of Tuvan music. He taught himself the sound he heard. Two years later, he finally made it to a concert.

The promoters? The Friends of Tuva. They never forgot Feynman's love of the unique culture, and his enthusiasm outlived him. They flew the master throat singer Kongar ol-Ondar into the states. Paul Pena approached Kongar after the show, and gave an impromptu demonstration of the art Kongar spent a lifetime mastering. Kongar was so impressed that the two became fast friends, touring the United States together and sharing their musical interests. Kongar invited Paul Pena to Tuva. His trip is documented in the film "Ghengis Blues."

Something happened in the late nineties. The Tuvan Invasion, you might call it. Passed along by word of mouth, Tuvan artists began touring the United States. First came Kongar, then groups like Huun Huur-Tu, Sainkho Namtchylak, and Shu-De.

And there you have it. That's how I ended up sitting in a rock club, listening to Soriah perform an art developed by shamans in Outer Mongolia, promoted by a physicist, and popularized by a blind blues man.

Now sit back and tell me that doesn't make you smile.

I'm sitting in a Portland, Oregon rock club. It's situated right smack in the middle of the downtown meat market. To the right of me is Voodoo Donuts. Gutter punks spange outside, grabbing a few bucks from the drunks attracted to the scent of bacon and glazing. To the left of me is a flophouse, the human overflow sleeping in the streets outside it. On a normal night, the club caters to bored frat boys and enterprising bank tellers, everyone dressed in their cleanest polo shirts, Axe so thick it smells like a Thai ladyboy exploded.

Tonight it's different. The club is filled with drifting incense. People crowd the stage, sitting on the floor indian style, necks aching to see the white robed performers. Passers by wander in, hoping for the usual drunken party, and stand struck dumb. The stage is lit from every angle by candles, and in the center sits a massive iron cross. The performers mournfully ascend the stairs to the stage. Which is appropriate, because I have it on good authority that the cross once belonged to a particular headstone in a particular cemetery.

The sound comes then, the groaning, resonant moan that pitches wildly. People glance around, trying to pinpoint the sound's origin. Part didgereedoo, part Gregorian chant, its a sound that doesn't originate so much as emanate from the stage. I turn to my friend, who sits with an ecstatic grin I must be sharing and say: "What is this?"

I'm ahead of myself by at least eighty years. Starting from the top--

If you're Richard Feynman, you're a genius physicist with a penchant for chicanery and the sensibilities of a Bohemian. He spent his spare time at the Los Alamos labs back during WW2 cracking safes, or tricking people into opening them and then claiming them cracked, which is just as good. He collected stamps, and as a stamp collector, the rarer and the stranger the better.

One night he asks a friends and fellow adventurer, "Whatever happened to Tannu Tuva?"

Back in 1927, a set of stamps were issued from the tiny Mongolian prefecture of Tannu Tuva. As a newly independent country, finally wresting their freedom from Imperial China, the next logical step was to issue a stamp. Somehow this stamp made its way around the world and into Feynman's hands.

This stamp stuck out to Feynman-- here, have a look.

Now, that might not be the exact stamp, but you get the idea. He decided that he had to know more about this place. Tannu Tuva -- it sounds like a fantasy realm. In fact, Feynman's friend thought it may well be made up. That was just the sort of thing Richard would do to people. He'd invent a country, a whole culture, and see how long he could trick people into believing in it. Did I mention this man worked on the atom bomb?

What followed that question is recorded in "Tuva or Bust!", by Ralph Leighton. Richard Feynman spent the rest of his life trying to visit Tuva. He collected scratchy field recordings of Tuvan music, old photos of Tuvan costumes, anything he could lay his hands on. He and his friends created the "Friends of Tuva" foundation to archive this knowledge, and it lives on today.

Now keep in mind this was the middle of the Cold War, and a former atomic scientist wanted entry into the Soviet Union. Even if the Soviets wanted him in, the State Department probably wasn't too keen to let an outspoken cultural critic like Feynman anywhere near Russia. And so his requests existed in an endless bureaucratic loop. Perhaps they were hoping he'd forget about it. Never underestimate the memory and tenacity of a man who remembered a postage stamp he'd seen a decade earlier. Feynman never gave up.

Finally the State Department relented. After nearly twenty years, they granted Richard Feynman the right to travel to Tuva.

Unfortunately, Feynman died of cancer the day before.

The world was poorer for the loss, but before he went, Richard Feynman taught thousands, earned Nobel Prizes in physics, became an outspoken proponent of science, and lived life with a wry smile and set of bongos.

Step back a little. There's someone else in this story.

Paul Pena was born with congenital glaucoma. His eyesight was bad at fifteen, and gone by twenty. It didn't slow him down--he learned to play music with an intimidating ease. By the mid seventies, right at the time Ralph Leighton and Richard Feynman were having their dinner discussions, he was playing with anyone who had a name in the blues community. Pick a name out of a hat, and Paul Pena played with them. B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Leon Redbone, Steve Ray Vaughn, Mississippi Fred McDowell, 'Big Bones,' John Lee Hooker and T. Bone Walker-- he even had a song of his recorded by the Steve Miller Band. Paul Pena was going up, and fast.

Then his wife, Babe, got sick--kidney failure. He dropped everything to take care of her. One night, December 29th, 1984 to be exact, Paul was listening to his shortwave radio. This isn't something people do too much these days, but if the air was just right and the night was clear you could hear broadcasts from all over the world. Paul was hunting for a Korean language lesson he'd heard.

Instead, he heard a Russian broadcast centered on the music of Tuva. That when he heard Tuvan throat singing. To a musician, specifically to a blues musician, that rumbling growl must have been a revelation. Two, sometimes three separate tones overlapped in one voice. This became an obsession for Paul.

For the next eight years he searched record stores high and low for this music. He asked musician friends, he tried to explain the unearthly sounds he heard that winter night. For eight years, no one had an answer for him.

It wasn't until 1991 that he found a CD of Tuvan music. He taught himself the sound he heard. Two years later, he finally made it to a concert.

The promoters? The Friends of Tuva. They never forgot Feynman's love of the unique culture, and his enthusiasm outlived him. They flew the master throat singer Kongar ol-Ondar into the states. Paul Pena approached Kongar after the show, and gave an impromptu demonstration of the art Kongar spent a lifetime mastering. Kongar was so impressed that the two became fast friends, touring the United States together and sharing their musical interests. Kongar invited Paul Pena to Tuva. His trip is documented in the film "Ghengis Blues."

Something happened in the late nineties. The Tuvan Invasion, you might call it. Passed along by word of mouth, Tuvan artists began touring the United States. First came Kongar, then groups like Huun Huur-Tu, Sainkho Namtchylak, and Shu-De.

And there you have it. That's how I ended up sitting in a rock club, listening to Soriah perform an art developed by shamans in Outer Mongolia, promoted by a physicist, and popularized by a blind blues man.

Now sit back and tell me that doesn't make you smile.

Comments

Post a Comment